The Progenitor’s Dilemma: Avoiding Entitlement When Transferring Wealth

A practical framework that empowers heirs while minimizing negative consequences

byline Doug Baumoel, Blair Trippe and Katie Spencer

Est. Read time: ~8 to 9 minutes

Wealth can, at times, feel more like a curse than a blessing. Wealth magnifies the impact of bad choices and presents dilemmas to those progenitors who must determine how to distribute their assets over their lifetimes and beyond. Perhaps the biggest fear among benefactors is transferring wealth in a way that engenders entitlement. Progenitors do not want affluence to crush the next-generation’s initiative, sense of purpose or self-esteem.

They also want to ensure that those receiving some of their wealth do not confuse self-worth with net-worth. This can be easier said than done in a world that responds strongly to the material. But if progenitors can understand the issues at play and how choices regarding transfer of their wealth may impact the recipients of that wealth, they will be better able to achieve the benefits they want for their next-gens and avoid some of the pitfalls they fear.

Many families feel uncertain about the potential consequences of wealth transfer, wondering:

How can I use my wealth to give my children opportunities but not make them entitled?

and

How much should I give, and when?

We have found that, when progenitors make informed decisions with intention, factoring in all the relevant issues at play, they are better able to avoid common pitfalls and increase the likelihood that their wealth transfer will be constructive, and not destructive, for future generations.

Please note that throughout this piece we will refer at times to parents or grandparents as progenitors and children as the recipients of wealth. We acknowledge that these relationships and roles are not the only ones to consider in the ‘progenitor’s dilemma’ and use them only as short-hand for readability of this piece. We do not mean to imply that these frameworks only apply to these roles. Whenever there is wealth transfer and a concern for its impact on the recipients, these frameworks apply.

Finally, the magnitude of the wealth at issue varies greatly across families. The concerns of parents and grandparents, however, seem consistent and informative of how much of their wealth they choose to transfer to each of their heirs regardless of the magnitude of that wealth. Of significance is not the dollar amount given, but the relative impact that the money has on the individual’s choices and lifestyle.

For many families, wealth is transferred both outright and in trust. For some, it is transferred as ownership of a business, real estate, or other assets, such as artwork. Our focus, and the basis on which this framework was developed, considers the liquid assets over which heirs would have some significant control, whether in trust or not.

In our experience, parents and grandparents typically have a sense of the magnitude of accumulated wealth that would likely be available to their heirs. They also have a rough idea of the percentage of that wealth which they intend to transfer to their children and grandchildren over their lifetime and what percentage might go to charity or other purposes. The question of ‘how much’ might be distributed, is often driven by tax implications and fairness considerations. The magnitude of wealth available also influences how much would be made available to each of the succeeding generations – ie, to what extent can the wealth benefit multiple generations, rather than the next generation alone.

These considerations are reasonably straightforward and are the primary determinants of ‘how much’ each heir will potentially receive. The more perplexing questions are the ‘when’ and ‘how’, because these are factors that have the most significant impact on heirs.

Also important is clarifying the impulse behind the transfer of wealth. In their book, Cycle of the Gift, Jay Hughes, Susan Massenzio and Keith Whitaker make a distinction between a gift and a transfer.

What makes a transfer of wealth a gift is that it is given with purpose, free of judgement, to express or reinforce emotional connection. A transfer has other motivations – to save taxes, to be fair, to influence behavior or to protect the asset from others. Understanding the difference between a gift and a transfer is an important first step for progenitors, so they may then clearly communicate their intentions regarding the wealth and establish appropriate expectations.

What determines the impact of wealth transfer?

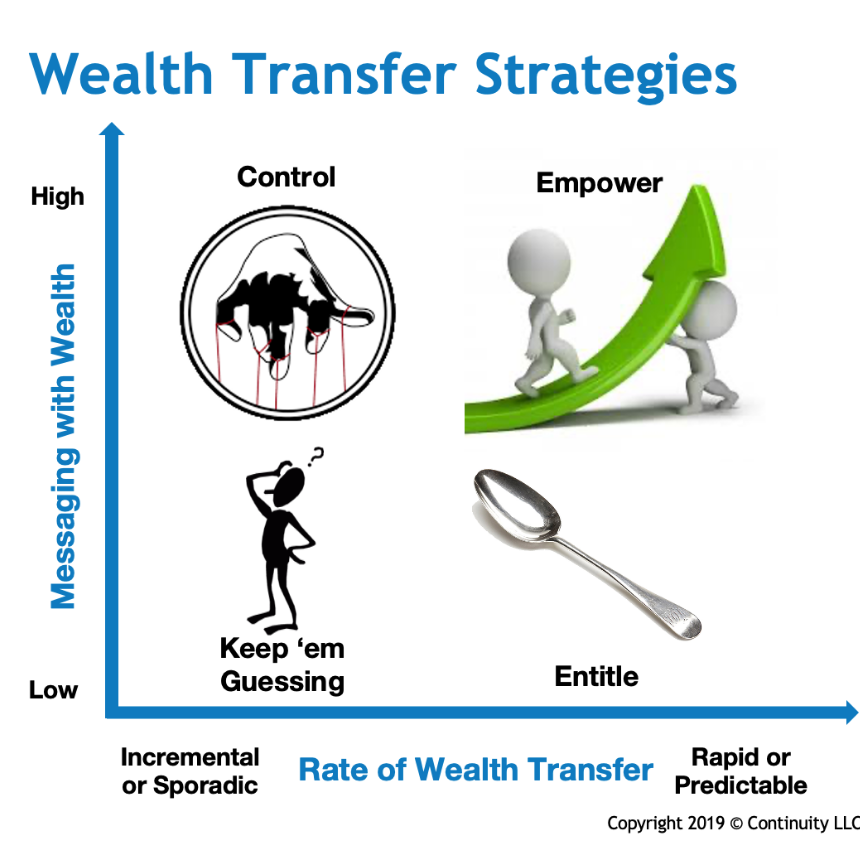

Our experience reveals that two factors influence how wealth transfer impacts beneficiaries: when wealth is transferred – specifically, the rate at which the expected lifetime transfer occurs; and how wealth is transferred, including the degree to which the transfer is accompanied by intentional messaging.

When, or at what rate, is wealth transferred?

Should wealth be given gradually over time, at specific milestones, or withheld until the progenitor’s death? Thinking in terms of rate, rather than date (or when) is more informative because rate combines both the ‘when’ and the ‘amount’ and is more relevant to addressing the progenitor’s dilemma. A high rate would represent a significant portion of the expected lifetime wealth transfer at regularly scheduled times throughout the receivers’ lives, generally before the heirs reach 50 years old. A low rate would be small amounts, with respect to what can be made available, given sporadically without much predictability – perhaps with the bulk of the transfer happening when the progenitor’s estate matures.

How is wealth transferred?

The degree to which wealth transfer is accompanied by intentional messaging has a tremendous impact on how it is received. How deeply does the progenitor consider and communicate the purpose of the transfer? Do they speak about the intended purpose of their wealth or how it should be used? Does the heir understand how the money was originally made or how much effort and sacrifice went into making it? Do they suggest that a transfer might be a test to determine how a child would use the money and how that assessment would impact what future gifts might be given?

What would represent a high level of intentional messaging would be situations in which parents sit down with their children to speak about their intentions for providing the wealth, teach their children to understand and manage their wealth productively, and provide some guidelines and accountability. For example, for younger children parents may suggest approaches such as spending 1/3, saving/investing 1/3 and donating 1/3; or they may suggest that with money comes certain responsibilities. They might offer resources such as a wealth adviser, trustee or other trusted adviser to help the increasingly wealthy recipient make informed choices.

A low level of messaging would be a situation in which heirs are simply informed that a transfer has been made or that now, upon reaching a certain age, they have access to a tranche of assets. Without appropriate messaging a child may not have an appropriate level of financial literacy, for example, and, like getting the keys to a car before learning how to drive, may be at risk of having a bad outcome.

The Framework

We compiled information from working directly with affluent families and created a framework to help families conceptualise common approaches used to transfer wealth. By plotting “rate of wealth transfer” on the x-axis and “degree of messaging” on the y-axis, we identified four approaches to wealth transfer from which we developed four archetypes: ‘keep ‘em guessing’, ‘control’, ‘entitle’, and ‘empower’. While the framework does not provide direct answers to the progenitor’s dilemma, it provides a useful way to think about the central issues and how actions and outcomes may be correlated.

The Four Archetypes

Keep ‘em guessing

Minimal messaging or communication is provided with the wealth given, and wealth is provided slowly or sporadically. There may be several reasons for taking this approach. If cash flow is uneven and/or uncertain, this may be a necessary way for a progenitor to transfer money without expectation of more to come. However, for families who can support more wealth transfer, this slow or sporadic pace is often motivated by concern (fear) that money will result in entitlement behavior.

Regardless of the motivation, the consequence of this behavior is that it makes it difficult for beneficiaries to take responsibility for and plan their financial lives. It prevents them from making significant and important investments in their futures. In addition, it may rob the recipient of the opportunity to feel grateful for the money, because the uncertainty, confusion and lack of accompanying empowerment may negate their appreciation of it. Indeed, when the recipient believes that wealth can (or should) be transferred more quickly, and receives minimal messaging regarding why wealth might be withheld, the recipient may feel resentment, rather than gratitude, for the transfer.

Control

Wealth is given slowly or sporadically, but with high messaging – typically describing specific, ‘approved’ purposes for the wealth. For example, wealth might be given to buy a new house in a particular neighborhood or for tuition for a specific school chosen by the progenitor. This approach to wealth transfer is used by the giver to control the choices and behaviour of the recipient through directives about what they can and cannot do with the money provided. Feeling controlled by the parent, the child may feel resentment, suspicious of what others are getting and whether they are being treated fairly.

In addition, some benefactors using this approach try to incentivise their heirs with access to additional funds by evaluating whether or not they ‘perform’ well with the current amount. While some children might thrive under this regime, others may take a safe route to avoid failure, foregoing a riskier path that might speak more to who they are and what they want to accomplish. Often, children are not aware of their parents’ or grandparents’ intentions or that the current transfer is a ‘test’, so they make uninformed or misguided decisions in their use of the wealth that might have been made differently had they understood the bigger picture.

Entitle

Wealth is given generously over the course of the heirs’ lives with minimal messaging. It can be given proactively or simply by request of the receiver. It is given freely for the recipient to do with it as they choose, presumably with the hope it will be used wisely, but with little guidance, preparation or accountability. This can lead to entitlement on the part of the receiver – a sense that he or she is owed privileges without responsibility or the need to earn them. This may not only damage their image in the family or their social network but may also squelch their motivation to pursue purpose in life. Should this happen, the progenitors bear some responsibility for failing to provide appropriate messaging with their transfer of wealth.

Empower

Recipients of significant wealth are more likely to become motivated to achieve if wealth is given thoughtfully and intentionally. When there is guidance and expectations of accountability, recipients can make more impactful, thoughtful and purposeful choices.

Heirs who are educated and prepared for the transfer are better able to self-actualise in a productive and meaningful way with the advantage and empowerment that money can provide. With proper messaging, recipients understand that the money is intended to offer them opportunities and to offer them certain benefits. They know that their basic needs will be met, so they are free to pursue their passion(s). The wealth, transferred with thoughtful planning and messaging, can encourage the recipient to engage through their lifetime and in their communities, not to disengage. As Warren Buffet famously said of his intentions regarding wealth transfer, he wanted to leave enough for his children to be able to do anything, but not enough for them to do nothing. While his famous quote speaks about ‘amount’, we believe that his message was about productivity.

Learning from the progenitor’s dilemma framework

Different motivations, assumptions and goals lead to different types of family wealth transfer strategies. By deconstructing the components of wealth transfer, parents can make more informed decisions regarding their wealth transfer strategies. The framework helps parents recognise that what they do to transfer wealth and how they do it has a significant impact on their children. Rather than just hoping for the best, parents can consider where they are in the matrix and design a path to get to where they want to be. Progenitors can be proactive regarding how they transfer their assets over time without falling into the trap of entitling (or controlling) the recipients of their wealth.

The intention of the framework is for families to discuss, individually and as groups, how transfers feel to them and if those transfers are being communicated properly. Moreover, the framework can be used to gauge outcomes, providing a standard by which givers and receivers can talk about the impact of a past transfer.

Messaging strategies

These strategies are far from exhaustive and are only meant to prompt creative thinking and assessment of what might work in any given family system. They are neither prescriptions nor judgements on what ‘should’ be messaged. Rather, they are meant as examples of how ‘messaging’ can be used in the framework.

Values: identification and communication

Children inherit far more than financial resources. The extent to which parents and grandparents model their values concerning wealth greatly influences the outcome of a wealth transfer. Thus, it is important for progenitors to ensure that these values are taught explicitly through conversation and implicitly through their own behavior. Values can be taught explicitly, for example, by teaching children how to allocate their allowance or income towards different things: share, save, spend, invest. This explicit lesson conveys the value of charitable giving.

An implicit lesson might be, for example, if a progenitor hopes that their beneficiaries will grow to be respectful individuals, they must model respectful behavior whether they are speaking to a colleague or a waiter. There are many values identification exercises available and consultants who can guide families through a process of operationalizing those values.

Family history and legacy

Communicating the history, hard work, and lessons learned regarding the family wealth is an excellent way to engage the next-generation and, hopefully, instil a sense of stewardship. When heirs truly understand the stories behind the money, they are more likely to treat the wealth with more care. Likewise, progenitors who clearly articulate their hoped-for legacy and share this with their beneficiaries are more likely to see wealth have a positive impact by setting expectations and desires for their wealth.

Some families focus on the entrepreneurial journey that created the wealth in order to communicate those values with the wealth. Others might talk about the fairness standards and teamwork that went into sustaining the wealth.

Financial engagement and education

It is important for parents to take a proactive stance on engendering first financial engagement, and then financial education. This is a long-term, intentional endeavour, and it can take time to see results. However, progenitors who recognise that this is a long-term process and act diligently and with patience, often see more engaged and skilful beneficiaries.

Increasing exposure to family finances over time and in an age-appropriate manner is a key entry point. Next-gens who have a healthy relationship with their resources often reflect on how their parents would invite them to sit with them while they managed the budget, paid bills and other monetary activities. As they aged, these individuals reflected on the benefits of ‘family bank’ type projects that their parents introduced. For example, if they wanted to buy a car, the parents would offer to match the amount that the child earned to go towards this purchase.

As heirs mature, include them in larger family financial decisions such as taking trips, buying/selling property, making a new investment, and deciding the strategy for (and reasons behind) paying for higher education.

Formal financial and business literacy training can be introduced at age-appropriate times as well. There are many resources for this training. Many can actually offer fun opportunities that engage multiple generations of the family.

Explicit and clear communication about money

One key to successful wealth messaging is to be as explicit and clear as possible in all communication about money. This sets up each person involved and the interpersonal dynamics for greater success. Be clear regarding the intention of every gift and transfer. Are there strings attached or are the resources to be used at the beneficiary’s complete discretion? If there are specific guidelines for how money is to be used, consequences for not following said guidelines, or other ‘strings’ involved in a financial transfer, they must be clearly stated. If there are conditions regarding a current gift, which determine future gifts, the beneficiary needs to know this. Letters of intention that are provided either independent of or in conjunction with trust documents are a useful way to ensure clear communication, particularly should the progenitor pass prior to having explicit conversations. This type of documentation not only provides beneficiaries with guidance that helps them integrate wealth into their life and identity, but can also become a critical piece of inheritance itself. Having your loved one’s words written specifically to you is a gift that few would not cherish.

Getting and giving permission

It is typically a parent’s responsibility and concern that their children make good decisions as they mature. Wealth can magnify the consequences of their decisions and for this reason many parents want to have control over the rate and messaging of wealth transfer. However, grandparents may be in a position to transfer wealth to their grandchildren without that parent’s involvement. In order to prevent miscommunication, conflict and working at cross-purposes, it is important that benefactors coordinate their wealth transfer if they are concerned for its impact on the heir. This requires forging alignment regarding the purpose of wealth transfer and its desired outcome among progenitors.

Support system

Setting up beneficiaries for long-term success often involves ensuring that they are connected to the advisers and other support people that they will need (now and in the future). Ensuring that the next- generation is not only aware of who their financial advisers, attorney and trustees are, but also facilitating in-person conversations between them is the gold standard. We have worked with clients, for example, who have the email address of their “parent’s financial adviser”, and feel uncomfortable and even inappropriate reaching out to them for a question. Developing these connections and building the relationships as early as possible greatly influences a beneficiary’s sense of agency in and ownership of their financial reality (ie, empowerment).

Mentorship is another way to offer support to beneficiaries. Connecting them with someone a few steps ahead of them in their wealth journey for peer- to-peer counsel and guidance can provide a safe space for exploring wealth that is nearly impossible to find in other friendships. If there are opportunities for beneficiaries to join cohorts of peers in similar positions, this can offer valuable support.

There are many coaches and consultants who can also support the family system and individual beneficiaries to prepare for and integrate wealth in a more mindful and ultimately successful way. These external service providers are often the most helpful individuals to involve when the wealth transfer is traumatic in nature. The untimely death of a progenitor, for example, can greatly complicate the process of wealth transfer and integration. Family conflict surrounding inheritance is another opportunity to seek outside support.

Leave a Legacy of Empowerment, not Entitlement

Entitlement of the next generation is one of the main concerns we hear from parents. Confusing and “too many strings attached” are what we often hear from their beneficiaries. Achieving the right balance between the opportunities and responsibilities that come from wealth is a challenge that requires vigilance and deliberateness on the part of progenitors. Most parents want to be generous with their wealth, and they want the best for their children. Many make the mistake of giving at a high rate to the next generation without enough forethought, preparation or accountability. This can get well-intentioned parents into trouble and can lead to unintended consequences, such as entitlement and irresponsible behavior by their children regarding wealth. Heirs want guidance without feeling that wealth is being used to control them. They understand the need for accountability, but they also need opportunities to make mistakes in order to learn.

The Benefit to Trustees

Trustees can use this framework to enhance their relationships with beneficiaries. In his research, Jay E. Hughes, Jr. found that 80% of beneficiaries polled believed their trusts and trustee relationships to be a burden. While there may be many reasons for this, much of the sense of burden stemmed from the trustee-beneficiary relationship being antagonistic or fraught, rather than collaborative. Insight from this framework can lead to a better understanding of the purpose of the trust by both the trustee and beneficiary and how their relationship can be more collaborative based on the intentions (or fears) of the grantor. In addition, having a common language in which to discuss accountability and messaging helps to put the importance of deliberate action around messaging on the radar with the grantor when considering wealth transfer planning.

Summary

Through being more intentional about what and how they give, parents can avoid unintentionally using wealth as a means to control and infantilise or in a way that breeds entitlement. Instead, they can make wealth transfer empowering to their heirs. More importantly, when parents and heirs discuss wealth transfer within the context of this framework, the options for wealth transfer and their potential outcomes become clearer and more meaningful.

With greater understanding, productive conversation can happen on these important topics, and the legacy has a greater likelihood of inspiring pursuit of purpose and being a force for good, as was intended.

An example of using the model

We were called in to help a family prepare for a meeting that we were to facilitate. The progenitors, in this case a married couple whose business had flourished, planned to reveal the value of their business (several hundred millions of dollars) to their four adult children, who were in their 40s.

In the weeks prior to the meeting, we had the opportunity to speak with each of the children to gauge what they knew about the business and family wealth, and their experience growing up in this family that had grown in affluence over their lifetimes.

We learned that none of the children had a sense of the company’s value – nor of their current or future ownership of it. Neither did they have a sense of the wealth their parents accumulated. We also learned that there were some very fraught, difficult relationships among the siblings.

One was ostracized from the sibling group for being mum’s favorite and for receiving extra financial support for a home and other lifestyle expenses. Another felt that he was given less financial support than the others, because he had left the family faith. Another sibling worked in the business in an executive capacity and shared in its success. Being a high earner, she had significantly more wealth than the others. Her siblings did not begrudge her her wealth, because they felt that she earned it. However, some were angry that mom and dad provided that opportunity to her and not to them.

In summary, many of their differences had their basis in wealth and wealth disparity. Most importantly, none of them, even the sibling working in the business, had any idea about the value of the company and what their ownership in that company meant or would mean in the future.

The company paid dividends sporadically and modestly – never enough to impact any of the children’s lifestyles. One sibling remarked: “It’s nice when it comes because it pays for season tickets for hockey. But it’s frustrating because I never know if I’m going to get the distribution at the time I need to commit to the tickets – and we really shouldn’t get them if the money isn’t going to arrive this year. I don’t dare ask – I don’t want to look like I’m expecting it or that I’m not grateful for what I’ve gotten in the past.” When we asked the siblings to estimate how much their family business was worth, their answers were around 10% of what they were to learn was the actual value.

We also spoke with the parents before the meeting. We learned they valued frugality and privacy, and how their biggest fear, as their business began to grow, was that the wealth – or the knowledge of the wealth – would spoil and entitle their children and lead to them being lazy and unproductive. When funds were distributed, the parents were careful to tell them exactly what it could, and couldn’t, be used for.

This family meetings had traditionally been fraught with jealousies, rivalries and conflicting values. People would storm out of rooms and not speak to each other for weeks afterwards. This time, the family hired us as facilitators hoping that this all-important meeting would go more smoothly. Everyone knew that at some point during the meeting, the family would be told the value of the business.

We began the meeting with an overview of our findings from our conversations – being careful to respect individual confidentiality. Subsequently, we introduced the Wealth Transfer Styles framework. We explained the ‘messaging vs rate’ construct and introduced the ‘keep ‘em guessing’ archetype. We were able to explain that in their desire not to entitle their children, they have kept important information from them that is necessary for them to be able to plan their financial lives. We talked about their lack of financial literacy and how that left them unprepared for any significant wealth.

We then presented the ‘control’ archetype and discussed how the strict rules that accompanied the minimal distributions that were given had the effect of infantilizing the children. They were not able to get real practice making decisions about wealth – to make mistakes from which they would learn. Because charitable giving was one of the conditions of the wealth transfer, the pleasure gotten from supporting personally meaningful causes was compromised because it felt forced for some.

When we introduced the ‘entitle’ archetype the parents were reassured that their wealth transfer strategies, while problematic, were better than entitling their children and having to deal with their biggest fear: having unproductive, out of control children who would make bad choices.

At that point, we stopped. We asked the parents if they identified with these archetypes and if they understood the trade-offs they have made. Because we were talking about archetypes, the parents were able to identify that their behaviour comported at times with these archetypes – but that these were not their intentions – to be controlling and secretive to the detriment of their children.

We asked the group – is there a fourth option for how wealth can be transferred which could have better outcomes?

When the ‘empower’ archetype was revealed on the screen, we could feel the coming together of the family; their collective “of course – why didn’t we think of that”, told us they were ready to learn how to empower their children with the wealth they were about to reveal.

At that point, with the parent’s permission, we revealed that the company value was more than 10 times any of the children’s estimation. We also revealed, with the help of their estate attorney also at the meeting, how each of the children would share in ownership now and in the future. The estate attorney walked through the trusts and explained how those trusts protected the company, but empowered families. All the in-laws in the room were grateful for being included in the discussion and appreciative of what the family was trying to do. Both a one-time significant distribution and a distribution policy was announced along with clear values and expectations around the purpose of that money – relieving each sibling and their families of current financial stress and resolving some of the wealth disparity that caused so much sibling conflict in the past.

When we came back to the framework, ideas for how wealth could be used to empower, not entitle or control the next gen were being shared. One daughter realized that she could take her home-based catering company to the next level with a small investment – and she understood that she would need to provide a business plan and that she would be held accountable to that plan. Other siblings shared how this unexpected gift could make them more productive or improve their lives in meaningful ways.

We were also able to have a discussion about faith and values that helped bridge the divide over religion. With the new feeling of abundance, rather than scarcity, the parents were able to talk about how their faith and values were imbued in the success of the family business. From that perspective, tithing seemed appropriate to all.

The Wealth Transfer Styles framework provided this family with a shorthand way of gauging future transfers and how they were used. The family was able to discuss where they each were on the chart – as a giver and as a receiver. This resulted in deeper discussions about wealth and its purpose for the family and enabled each of the siblings to thrive in a way their parents could not imagine.

Stay in the Know

Get our latest articles, tips, and insights delivered straight to your inbox.

Share this Insight, choose your platform!

About Us

Continuity Family Business Consulting is a leading advisory firm for enterprising families. Using a full suite of service capabilities, we help families prevent and manage the single greatest threat to family and business continuity: conflict. It is through this lens that we advise our clients and build customized strategies for succession planning, corporate governance, family governance, and more. We help families improve decision making, maximize potential and achieve continuity. To inquire, contact us.