Resolving Extreme Conflict in Family Enterprises

A New Model for Understanding and Addressing Conflict in Family Business

By Doug Baumoel and Blair Trippe

Estimated read time: Approx. 12 mins

Conflict is inevitable in family enterprises, where personal, professional and ownership interests interact. While healthy disagreements can lead to innovation and growth, conflicts that spiral into negativity and hostility pose serious risks to both the business and family harmony.

For decades, the Thomas–Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TK Model) has been a cornerstone for understanding and managing conflicts. However, it falls short in addressing the more extreme, emotionally-charged conflicts that arise in family enterprises. Recognizing this gap, we developed a much-needed extension to the TK Model, a unique methodology tailored to address these intense, identity-based conflicts.

The TK Model: A Foundational Model for Conflict Negotiation

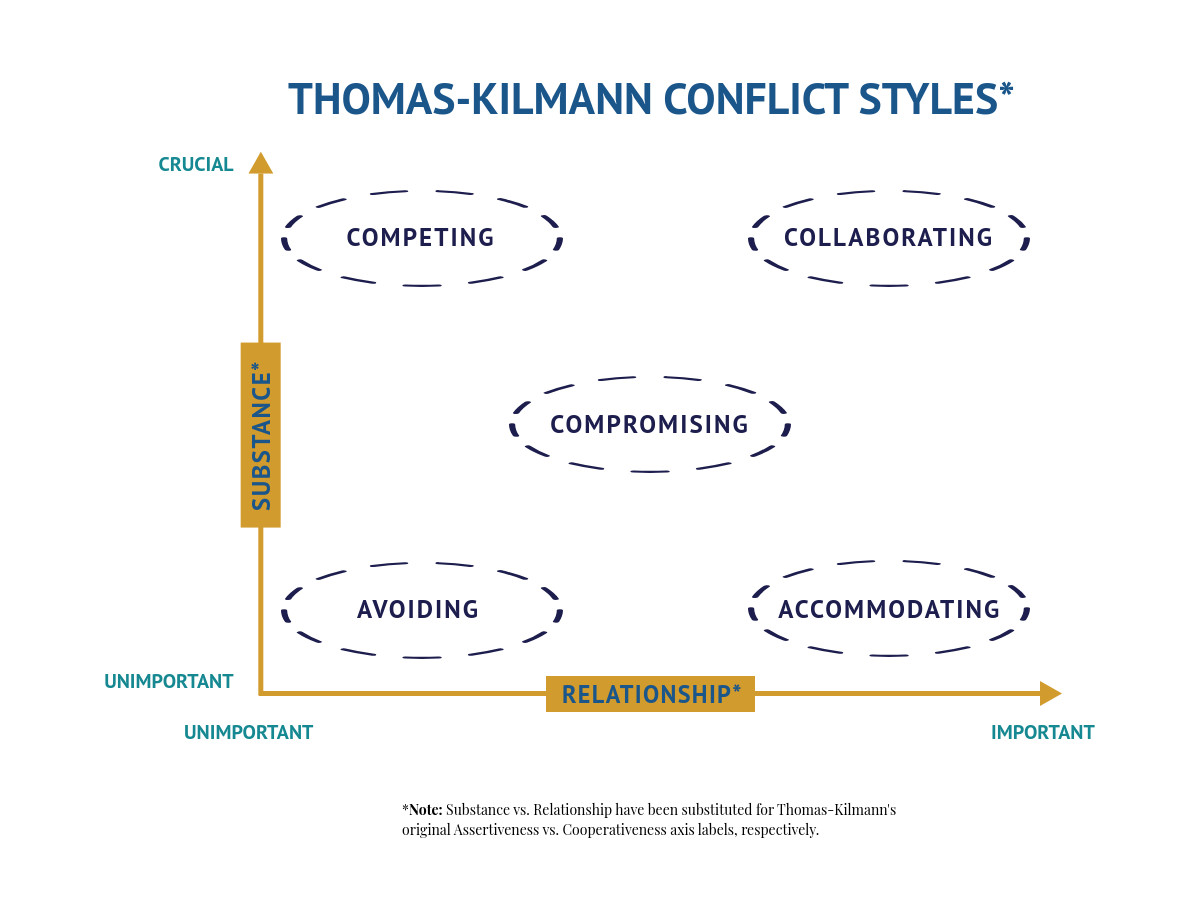

The TK Model was introduced in 1977 as a tool to help negotiators and mediators understand how individuals make decisions when they have competing interests. The model was built on two key dimensions:

- Assertiveness: How strongly a person pursues their own interests

- Cooperativeness: How willing a person is to accommodate the interests of others

In practice, “assertiveness” in the TK Model is often interpreted as an indicator of how important the substantive issue — the core disagreement — is to each party. Similarly, “cooperativeness” is understood as a measure of how important the relationship is to each party in the dispute. As a result, the model is frequently presented as a framework for evaluating the relative importance of the “Substance” of a dispute versus the importance of the “Relationship” between the individuals involved. For clarity, we will adopt this interpretation of the TK Model in our approach.

These dimensions create a matrix of five conflict-handling styles:

- Avoiding: Low assertiveness, low cooperativeness

- Competing: High assertiveness, low cooperativeness

- Accommodating: Low assertiveness, high cooperativeness

- Compromising: Moderate assertiveness, moderate cooperativeness

- Collaborating: High assertiveness, high cooperativeness

Example: Car Shopping vs. Birthday Dinner with Grandma

When shopping for a car, the substantive issue — price — is of paramount importance, while the relationship with the salesperson is short-term and relatively unimportant. In this scenario, a car shopper is likely to adopt a competitive negotiation style (competitive behavior), prioritizing getting the best deal over maintaining rapport with the salesperson.

In contrast, consider the decision of where to take Grandma for her birthday dinner. Even if the grandchild dislikes Grandma’s preferred restaurant or isn’t in the mood for that type of cuisine, they are likely to accommodate her choice. Here, the relationship holds far greater importance than the specific dining preference, leading to a more cooperative approach.

This model has proven valuable in negotiation and mediation by providing a framework for analyzing behaviors and encouraging constructive approaches. Graphically illustrating where behaviors fall on the matrix helps disputants and mediators understand how stakeholders approach conflict based on their values and priorities.

Limitations of the TK Model

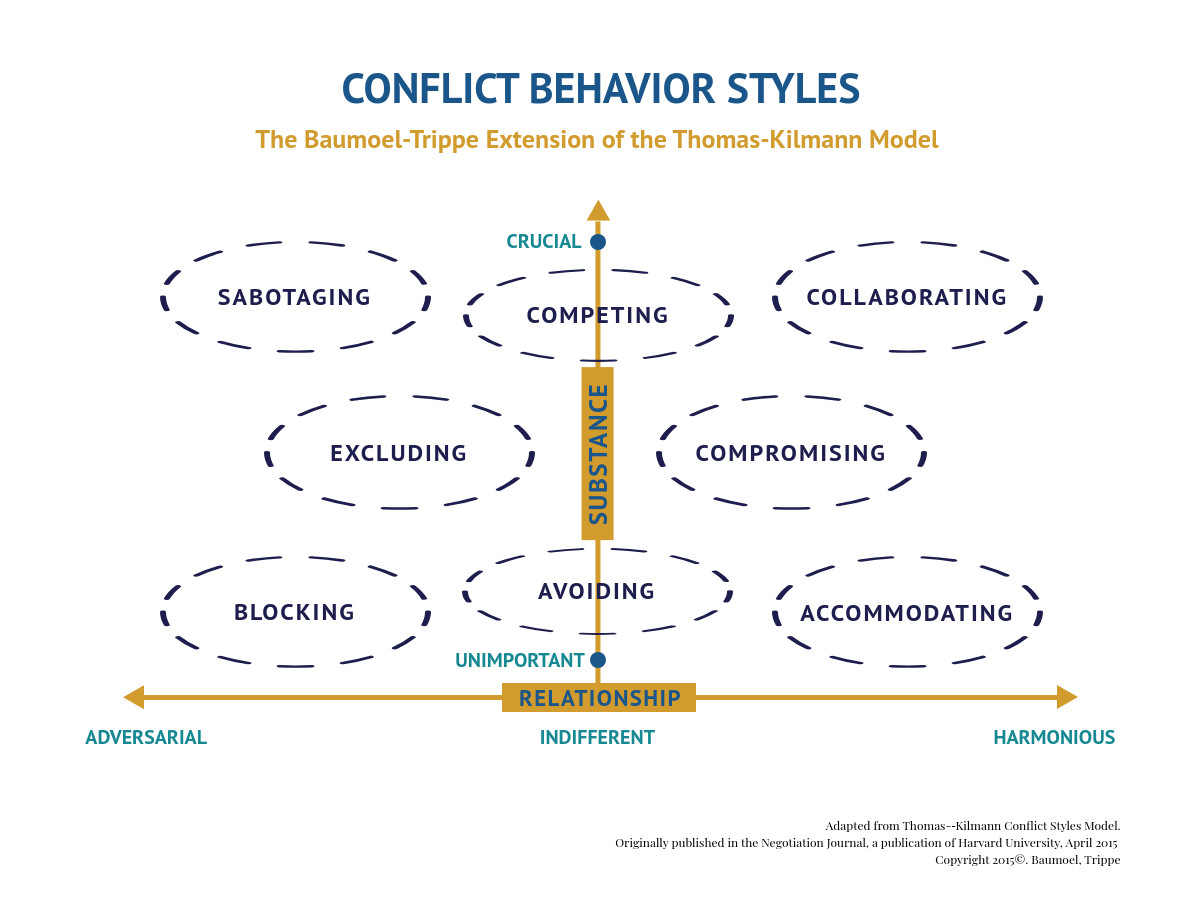

Despite its utility, the TK Model does not account for conflicts where relationships are not just unimportant or cooperative, but actively negative or adversarial. In family enterprises, where conflicts often involve high-stakes substantive issues and deeply personal dynamics, negotiation behaviors can become destructive. Therefore, the model must consider a broader range of relationships—from adversarial to harmonious—to be truly effective in these environments.

For example:

- What if one party seeks to block another’s progress out of spite?

- What if the conflict is fueled by deep-seated resentment or long-standing grievances?

- How do you address situations where the relationships themselves are the primary source of conflict rather than the substantive issue in dispute?

The TK Model assumes that when relationships are valued, they are inherently positive or neutral. However, in many family enterprise disputes, longstanding emotional wounds, power struggles, and perceived threats to identity drive conflict. Without a framework for navigating adversarial relationships, traditional models fall short in helping families resolve these deeply entrenched issues.

Why a New Methodology Was Needed

In family enterprises, relationships are often more complex and emotionally charged than in non-family businesses. Conflicts frequently involve deeply personal issues such as identity, legacy, and belonging. These dynamics create a unique challenge:

- Family members may feel “trapped” in conflicts, unable to resolve substantive issues without damaging their familial relationships. This often leads to disputes that persist for decades.

- Resentments can fester across generations, with new family stakeholders inheriting the unresolved conflicts and divisions of those who came before them.

Recognizing these challenges, we developed a new methodology as an essential extension to the widely accepted TK Model. This framework addresses the limitations of the original model by focusing on extreme conflict scenarios where relationships are actively negative or adversarial.

Introducing Continuity’s Methodology: A Practical Understanding of Extreme Conflict

Our methodology – the Baumoel-Trippe extension (BT-TK Model) – builds upon the TK framework by incorporating conflict behavior styles that emerge in adversarial relationships. It introduces new dimensions of conflict resolution specifically designed for family enterprises, including:

- Blocking: Behavior aimed solely at thwarting another party’s efforts, even when the substance of the issue is not important to the blocker

- Exclusion: Deliberate efforts to exclude others from decision-making or information-sharing to diminish their influence

- Sabotage: Actions taken to undermine another party’s efforts while advancing one’s own interests

How the BT-TK Model Works

Like the TK Model, this methodology helps individuals choose behavioral approaches to disagreement based on the nature of the relationship and the importance of the substantive issue in dispute. However, in cases of extreme conflict, individuals often act emotionally rather than following a rational strategy for achieving their goals. In practice, this model is particularly useful for identifying and addressing problematic conflict behaviors by naming them and exploring both the underlying relationship, and the substantive issues that triggered the response.

During a facilitated conversation, destructive behavior patterns — such as blocking, excluding or sabotage — can be recognized and discussed in the context of their root causes. This process often serves as a wake-up call, encouraging stakeholders to confront the emotional drivers of their actions and work toward resolution.

An Important Nuance in Family Business Conflict

Family business stakeholders often hurt each other deeply during conflict—not necessarily out of malice or self-interest, but because they believe they are protecting the business and its future. In many cases, stakeholders actually want the same things: they want their shared enterprise to succeed, they want to create wealth, and they want opportunities for all involved.

However, when individuals believe that their approach is essential to achieving those goals—and that others’ approaches pose an existential threat—they may go to great lengths to not only advance their own strategy but to block others from making what they perceive as harmful decisions. Ironically, what appears to be antagonistic behavior is often driven by a misguided sense of benevolence—a desire to “save” the other party from themselves.

When this dynamic occurs, it can be very helpful for stakeholders — who genuinely want the best for all involved — to recognize the inefficiency and destructiveness of their behavior. The BT-TK model helps expose these behaviors, providing a structured way to identify conflict patterns, realign around shared interests, and shift toward a more objective, problem-solving approach.

How the BT-TK Model Can Be Applied

Naming the problem is often the first step in resolving it. Identifying behaviors such as blocking, excluding and sabotaging can help family business stakeholders recognize destructive patterns in their conflicts. Few would argue that these behaviors — whether intentional or reactive — are productive for a company or its relationships.

Family stakeholders can generally agree that moving from the left side of the BT-TK Model to the right — shifting from adversarial relationships to more harmonious ones — would benefit both the business and its stakeholders. Reaching an agreement on the need to ‘move to the right’ is a critical step. Once this shared understanding is established, the real work of change can begin.

The model itself does not prescribe techniques for relationship repair, nor does it dictate how to improve communication. Instead, it serves as a powerful diagnostic tool, helping stakeholders identify behaviors associated with conflict and those linked to more constructive, collaborative relationships. By recognizing these patterns, stakeholders can take the next step—whether through better communication, improved dispute resolution skills, openness to new perspectives, or engaging in a process of forgiveness and healing past wounds.

Case Study: From Crisis to Collaboration in a Family Business

Background:

A family-owned manufacturer of high-performance sporting equipment was co-managed by four cousins. The two older cousins preferred maintaining the status quo, believing the company was stable and profitable enough. The two younger cousins, however, saw the need for innovation and expansion to remain competitive.

The Conflict:

The older cousins resisted the younger cousins’ proposals, fearing financial risk and exposure of their outdated management practices. Tensions escalated into destructive behaviors:

- The older cousins sabotaged the younger cousins’ plans by using their banking connections to block a loan for new facilities.

- The younger cousins retaliated by excluding the older cousins from meetings and communications.

As the conflict grew, trust eroded, and the business began to suffer. Employee morale declined, decision-making stalled, and the company’s market position weakened.

Applying Our Methodology:

- Identifying Behaviors: We recognized patterns of blocking, exclusion, and sabotage on both sides. Visual mapping of these behaviors helped the cousins understand how their actions contributed to the escalating conflict.

- Facilitating Dialogue: Neutral meetings allowed each cousin to share their fears and aspirations. The older cousins expressed concerns about financial stability, while the younger cousins emphasized the need for innovation to ensure long-term growth.

- Building Trust through Transparency: Clear policies for decision-making and governance were established, including the addition of independent board members to provide unbiased oversight.

- Crafting a Shared Vision: The family developed a phased innovation plan that balanced growth with risk management. This plan respected the older cousins’ need for stability while empowering the younger cousins to pursue innovation.

Outcome:

By addressing the emotional roots of the conflict and developing a shared vision, the family transformed their adversarial relationships into productive collaboration. The business regained its competitive edge, and family harmony was restored.

Conclusion: A Path Forward for Family Enterprises

Conflict is an inevitable part of family enterprises, but it doesn’t have to be destructive. Our unique methodology equips families with the tools to rebuild trust, foster collaboration, and secure long-term success. For a deeper understanding of this approach, we invite you to explore Deconstructing Conflict: Understanding Family Business, Shared Wealth, and Power. This book provides an in-depth look at the principles and strategies that can transform even the most challenging conflicts.

If your family enterprise is navigating extreme conflict, don’t hesitate to reach out. We’re here to help you achieve clarity, resolution, and a stronger future for your business and family.

Stay in the Know

Get our latest articles, tips, and insights delivered straight to your inbox.

Share this Insight, choose your platform!

About Us

Continuity Family Business Consulting is a leading advisory firm for enterprising families. Using a full suite of service capabilities, we help families prevent and manage the single greatest threat to family and business continuity: conflict. It is through this lens that we advise our clients and build customized strategies for succession planning, corporate governance, family governance, and more. We help families improve decision making, maximize potential and achieve continuity. To inquire, contact us.